Setting targets

The focus on strict numerical targets for hypoglycaemic control has changed in recent years, allowing greater flexibility in recognition of the needs of individuals.1

Reducing HbA1c levels is associated with a reduction in microvascular and macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes.2 Although several studies have demonstrated benefits of intensive glycaemic

control in terms of cardiovascular risk and other outcomes, there is also some evidence that very low targets (46mmol/mol, 6.4%) may be associated with increased mortality.2

There is consensus between national (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN]) and international guidelines (American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of

Diabetes [ADA/EASD]) that a ‘reasonable’ HbA1c target for most adult patients with type 2 diabetes would be 53mmol/mol (7.0%).1-3

NICE defines good glycaemic control as an HbA1c of 53mmol/mol (7.0%), but stresses the importance of tailoring targets to the individual, to somewhere between 48mmol/mol (6.5%) and 53mmol/mol (7.0%).3

SIGN also recommends a target of 53mmol/mol as reasonable to reduce the risk of complications, but suggests that a more stringent target (48mmol/mol [6.5%]) may be appropriate at diagnosis.2

It is important to balance benefits with potential harms, including the risk of hypoglycaemia and weight gain,2 and to involve patients in decisions about targets.3

The ADA/EASD consensus statement also recommends setting individualised glycaemic targets based on patient preferences and goals, the risk of adverse events (hypoglycaemia and weight gain), and patient characteristics, including frailty and comorbid conditions.1

NICE3 recommends that clinicians should consider relaxing the target HbA1c

level, on a

case-by-case basis for people with

type 2 diabetes who are older or frailer if they are:

-

Unlikely to achieve longer-term risk-reduction benefits, for example people with a reduced life expectancy

-

At increased risk of the consequences of hypoglycaemia as a result of tight blood glucose control, e.g.

-

People who are at risk of falling

-

People who have impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia, and

-

People who drive or operate machinery as part of their job

-

Suffering from significant comorbidities, for example, for whom intensive management would be inappropriate.

In the self-assessment that follows, hypothetical case scenarios based on fictitious

patients are presented. Please refer to the

relevant Summary of Product Characteristics before prescribing any of the medications

mentioned.

Boehringer Ingelheim has no control of the content of the

external

websites listed in References below.

References

-

Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin F, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes

(EASD). Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669-2701

-

SIGN SIGN154. Pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes, 2017. https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1090/sign154.pdf [Accessed March 2022]

-

NICE NG28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management, 2015 (2022 update). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28 [Accessed March 2022]

Achieving and maintaining control

Patients should be encouraged to achieve and maintain agreed targets unless any adverse effects, including hypoglycaemia, or their efforts to achieve their target, impair their quality of life.1

NICE suggests that the target for HbA1c for individuals whose type 2 diabetes is managed by lifestyle and diet, or by lifestyle and diet combined with one drug that does not have an associated risk of hypoglycaemia is 48mmol/mol. For those who are treated

with a drug associated with hypoglycaemia, the higher target (53mmol/mol [7.0%]) is recommended.1 If HbA1c levels are not adequately controlled by a single drug, and rise to 58mmol/mol (7.5%)

or higher, the addition of a second glucose lowering drug is recommended, alongside reinforcing advice on diet, lifestyle and adherence to drug treatment. These patients should be supported to aim for an HbA1c level of 53mmol/mol

(7.0%).1

In the self-assessment that follows, hypothetical case scenarios based on fictitious

patients are presented. Please refer to the

relevant Summary of Product Characteristics before prescribing any of the medications

mentioned.

Boehringer Ingelheim has no control of the content of the external

websites listed in References below.

References

-

NICE NG28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management, 2015 (2022 update).

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28 [Accessed March 2022]

First and second intensification

When considering intensification of treatment it is important to discuss options for treatment intensification first. These discussions should cover potential adverse events, adherence to existing medicines, the need to look at diet and exercise advice and the doses and formulations of current treatments.1

If the patient still requires further interventions, consideration should be given to:1

-

a DPP-4 inhibitor

-

pioglitazone

-

a sulphonylurea

-

an SGLT2 inhibitor

If dual therapy is unable to keep the patient under their agreed threshold, the addition of a DPP-4 inhibitor, pioglitazone, a sulphonylurea or an SGLT2 inhibitor should be considered or alternatively, insulin-based treatment should be started.1

In the self-assessment that follows, hypothetical case scenarios based on fictitious

patients are presented. Please refer to the

relevant Summary of Product Characteristics before prescribing any of the medications

mentioned.

Boehringer Ingelheim has no control of the content of the external

websites listed in References below.

References

-

NICE NG28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management, 2015 (2022 update). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28 [Accessed March 2022]

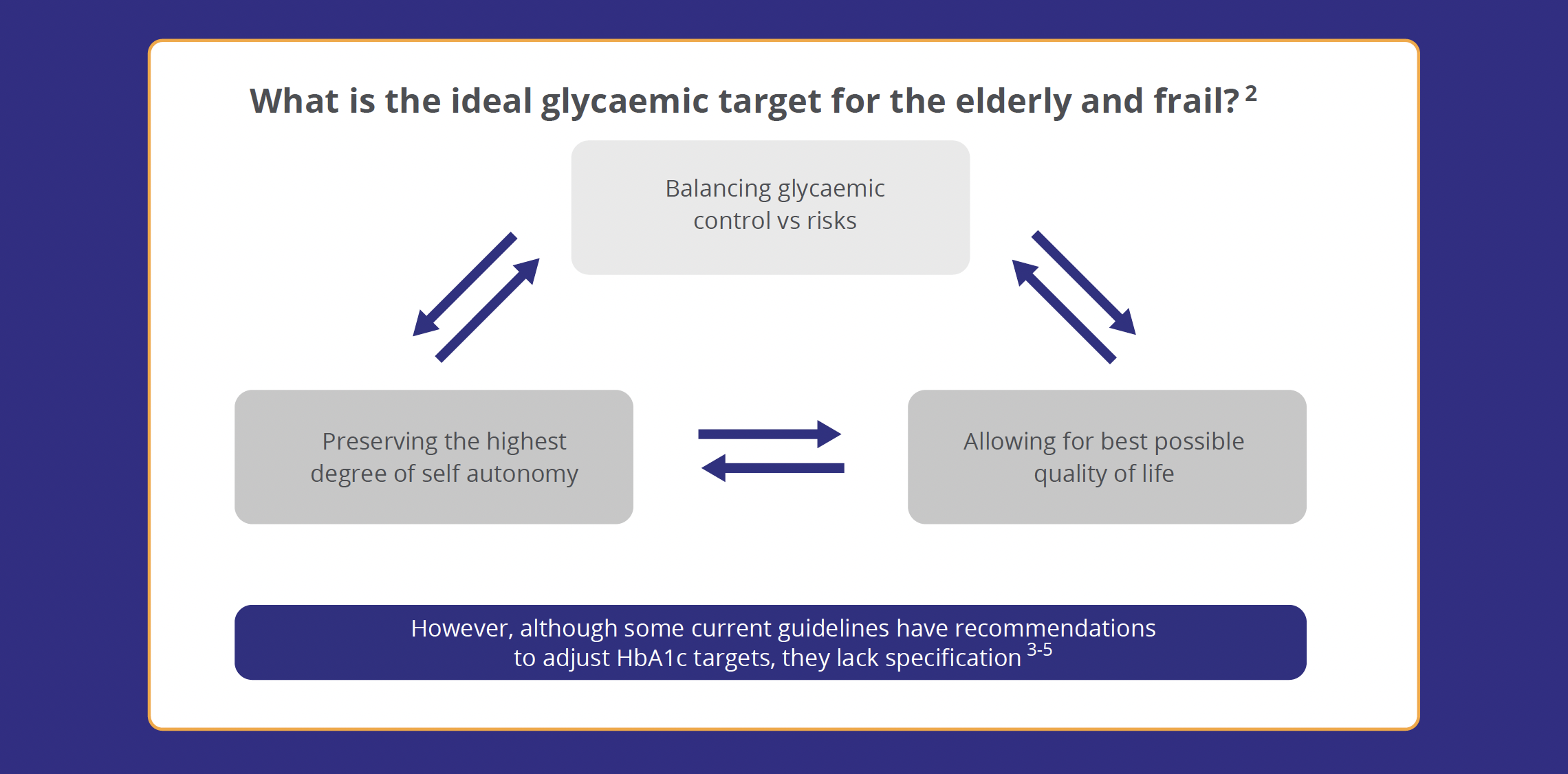

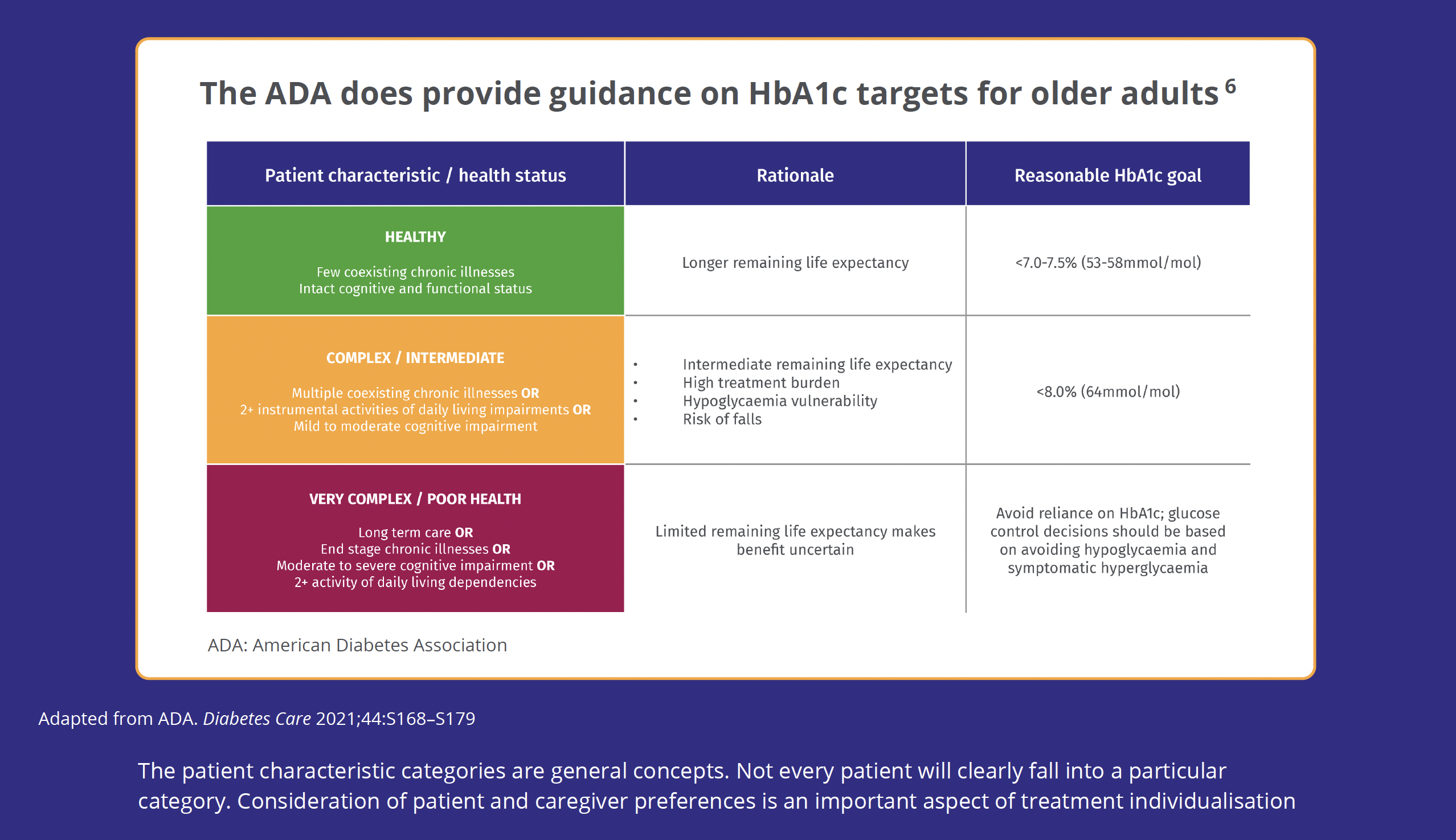

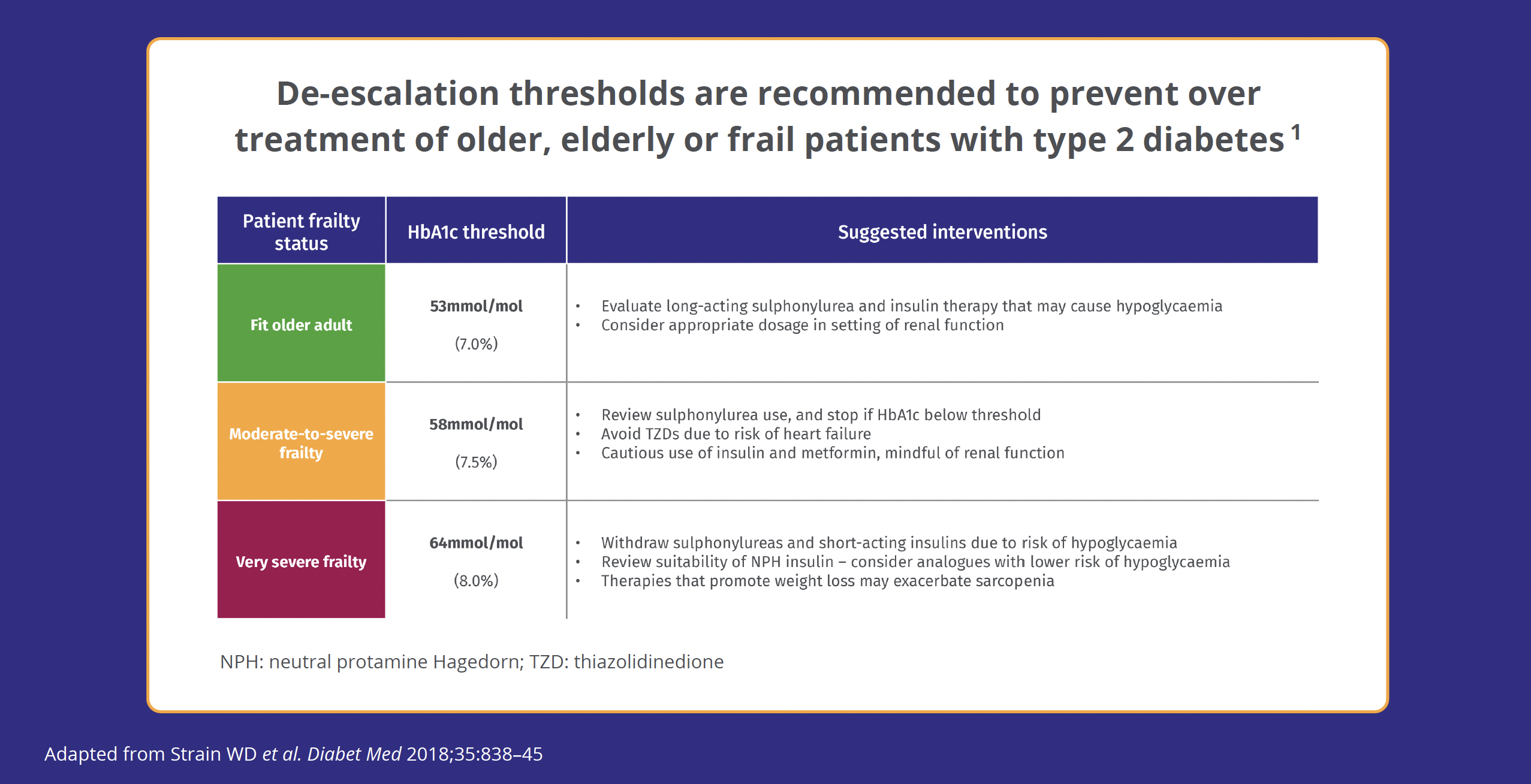

Frail and/or elderly patients

There is growing recognition that intensive glucose-lowering treatment in type 2 diabetes has limited benefits and may even be dangerous in older people.1 This should prompt clinicians to modify HbA1c targets in patients

who are very frail or have limited life expectancy. Guidance developed by the University of Exeter Medical School in collaboration with NHS England recommends a target of 64mmol/mol (8.0%) for adults with moderate frailty, and

70mmol/mol (8.5%) for the very frail, elderly patient. The guidance warns that metformin may be contraindicated in up to 50% of frail or very frail elderly patients who are likely to have a degree of renal impairment.1 Other agents, including sulfonylureas, pioglitazone, GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors may all have disadvantages in frail, elderly patients. DPP-4 inhibitors have been used in frail and elderly patients, and have similar

efficacy in older patients to that in younger populations.1

Frailty is fast becoming a critical complication for healthcare professionals to consider, when managing older people and their type 2 diabetes, providing that it has actually been identified for an individual patient. Now more than ever there needs to

be clear guidance and support for healthcare professionals in managing this group, especially as the numbers will continue to grow as the population ages.

In the self-assessment that follows, hypothetical case scenarios based on fictitious

patients are presented. Please refer to the

relevant Summary of Product Characteristics before prescribing any of the medications

mentioned.

Boehringer Ingelheim has no control of the content of the external

websites listed in References below.

References

-

Strain WD, Hope SV, Green A, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older people: a brief statement of key principles of modern day management including the assessment of frailty. A national collaborative stakeholder initiative.

Diabetic Med 2018;35(7):838-245

-

Abdelhafiz A, Koay L, Sinclair A. Frailty and hypoglycaemia in older people with type 2 diabetes: therapeutic implications. J Diabetes Nurs 2016;20:330–331

-

NICE NG28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management, 2015 (2022 update). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28 [Accessed March 2022]

-

SIGN SIGN154. Pharmacological management of glycaemic control in people with Type 2 Diabetes, 2017. Available at https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/qrg116.pdf [Accessed March 2022]

-

Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin F, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes

(EASD). Diabetologia 2018;61:2461–2498

-

ADA. Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care 2021;44:S168–S179